By Tonnie Iredia

In precolonial Africa, societal values such as honesty, respect, and fairness were firmly rooted in shared norms and beliefs that promoted healthy communal living. These values were widely upheld, and there was little need for written laws or formal sanctions to enforce them.

Perhaps the most powerful force sustaining these values was the fear of social stigma. No one wished to belong to a family condemned by the wider community for misconduct capable of attracting collective disapproval. In those days, a good name—rather than wealth—determined a person’s acceptance in society. Put differently, the credibility of one’s family served as the strongest guarantee of personal integrity.

As a result, individuals were careful not to engage in behaviour that could tarnish their family’s reputation. Formal instruction in ethics was often unnecessary, as moral conduct was learned naturally through everyday life at home. Elders would sometimes tell younger relatives embarking on journeys that the only gift they desired in return was a “good name.”

Unfortunately, the principle of accountability introduced by colonial administrators never gained the same moral authority as Africa’s indigenous value system, which was anchored in shared norms and collective responsibility. The European model relied on technical rules, procedures, and sanctions that lacked the cultural depth and emotional force of the traditional African system.

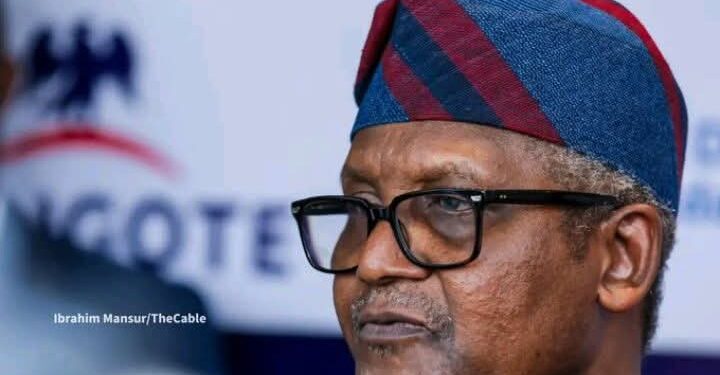

It is against this background that one must consider the allegation made by Aliko Dangote, Africa’s richest man, that the Chief Executive of the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), Engr. Farouk Ahmed, spent over $5 million on the foreign secondary education of his four children in Switzerland.

Dangote’s intervention stood out because he avoided the technical language of accountability. Instead, he appealed to a core African value that frowns on living above one’s legitimate means. In essence, he was calling for renewed seriousness in the fight against corruption—a struggle that has too often targeted appearances rather than substance.

Some analysts argue that Dangote’s advocacy is not entirely altruistic. They may have a point, but this argument is largely irrelevant. If a regulator appears intent on suffocating a businessman, should the latter suffer in silence? More importantly, the central issue here is public interest.

Should citizens support a regulator that prioritises importation—long regarded as a major weakness of Nigeria’s economy—over local production? Does one need to be an economist to understand the importance of protecting local industries and the employment opportunities they create? Why does the oil industry seem reluctant to regard Dangote as a patriot? Do they prefer wealthy Nigerians who invest their capital abroad?

What makes Dangote’s allegation particularly persuasive is the widespread perception that Nigeria’s public service has degenerated into an unethical jungle. Many citizens are frustrated by public officials who eagerly anticipate gratification before performing their duties. Others go further by openly demanding instant rewards. A third group engages in outright extortion, deliberately withholding services until bribes are paid.

Often, these bribes are so excessive that one begins to wonder whether one is dealing with a contractor rather than a public servant already paid from the public treasury. In effect, citizens are compelled to pay officials to carry out duties for which they are already salaried.

The argument that inadequate public-sector wages justify such conduct is weak. Extortion is not a lawful means of increasing income. Instead, it fuels inflation, as victims of extortion seek ways to recover their losses, thereby distorting the social and economic system. Many public servants fail to realise that they are active contributors to the rising cost of living in their environment.

While other sectors may also play a role, urgent steps must be taken to end the trading culture in public offices. Public offices are not marketplaces, and public servants are not traders.

Although it may be difficult to reverse this trend completely, we can at least begin with what is already known. Painfully, despite knowing what public officers are legitimately expected to earn, we frequently observe lifestyles their official incomes cannot sustain—yet we do nothing. The reality is clear: many public servants are deeply involved in stealing public resources.

![Popular Small-Size Actress Aunty Ajara Dies After Liver Illness [VIDEO]](https://thepunchng.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/20241109_125042-75x75.jpg)